FOTM Gare Joyce is responsible for the following words about Peter Robbins, the voice of Charlie Brown. Thank you Gare for letting me publish this brilliant prose on my little blog.

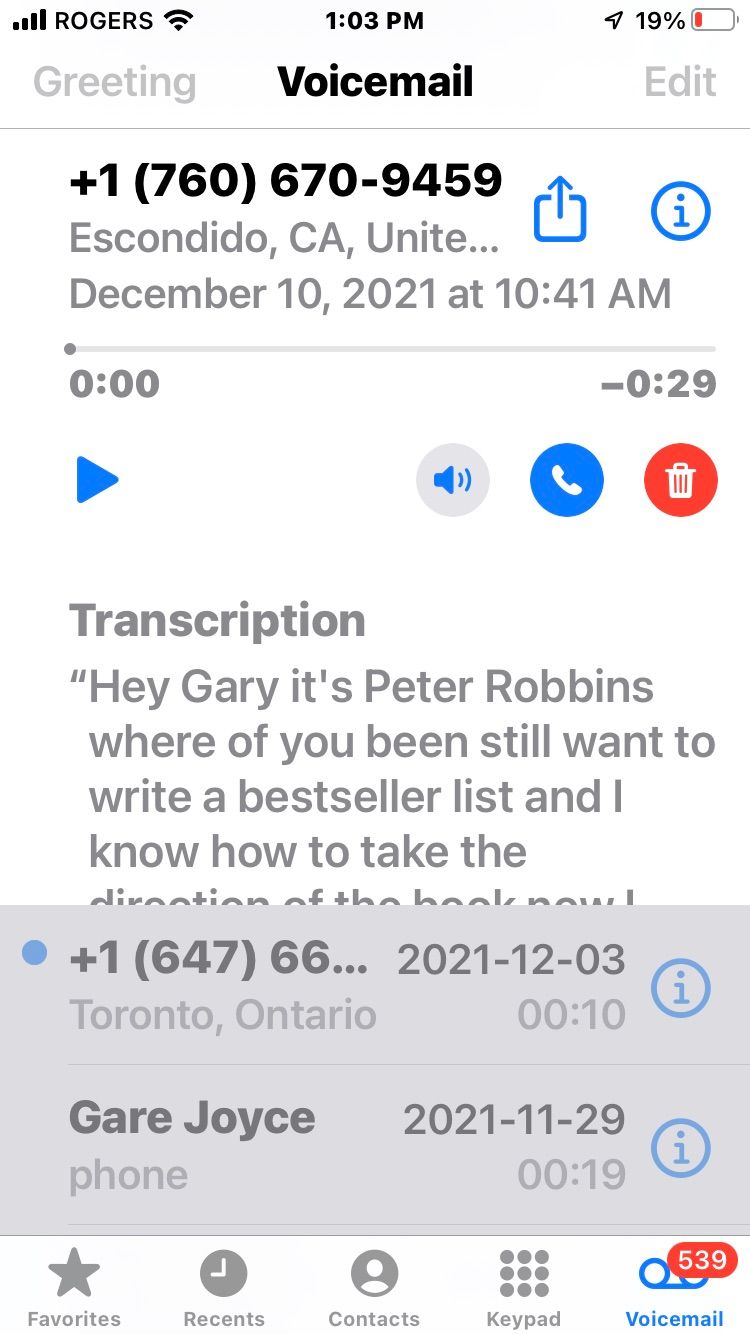

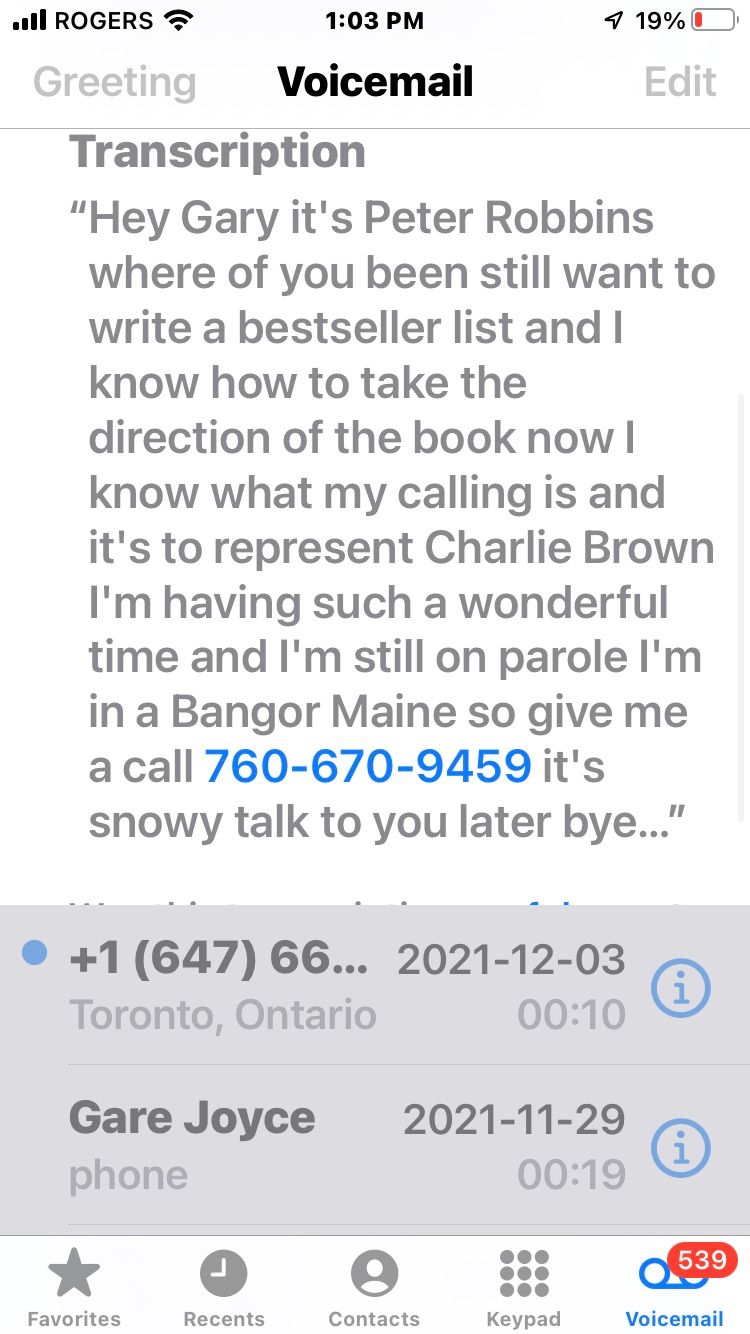

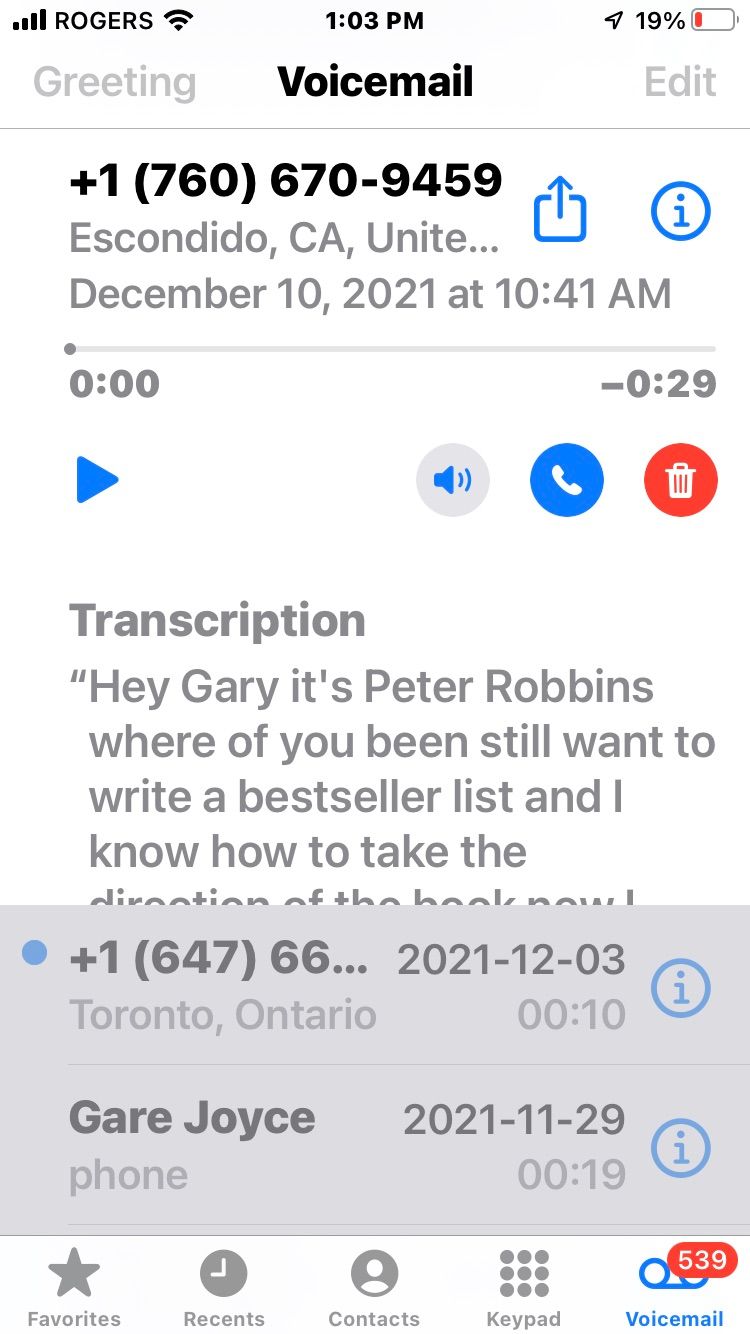

I’ve saved his voicemail. You wouldn’t recognize the voice, but U might think U had heard it somewhere be4

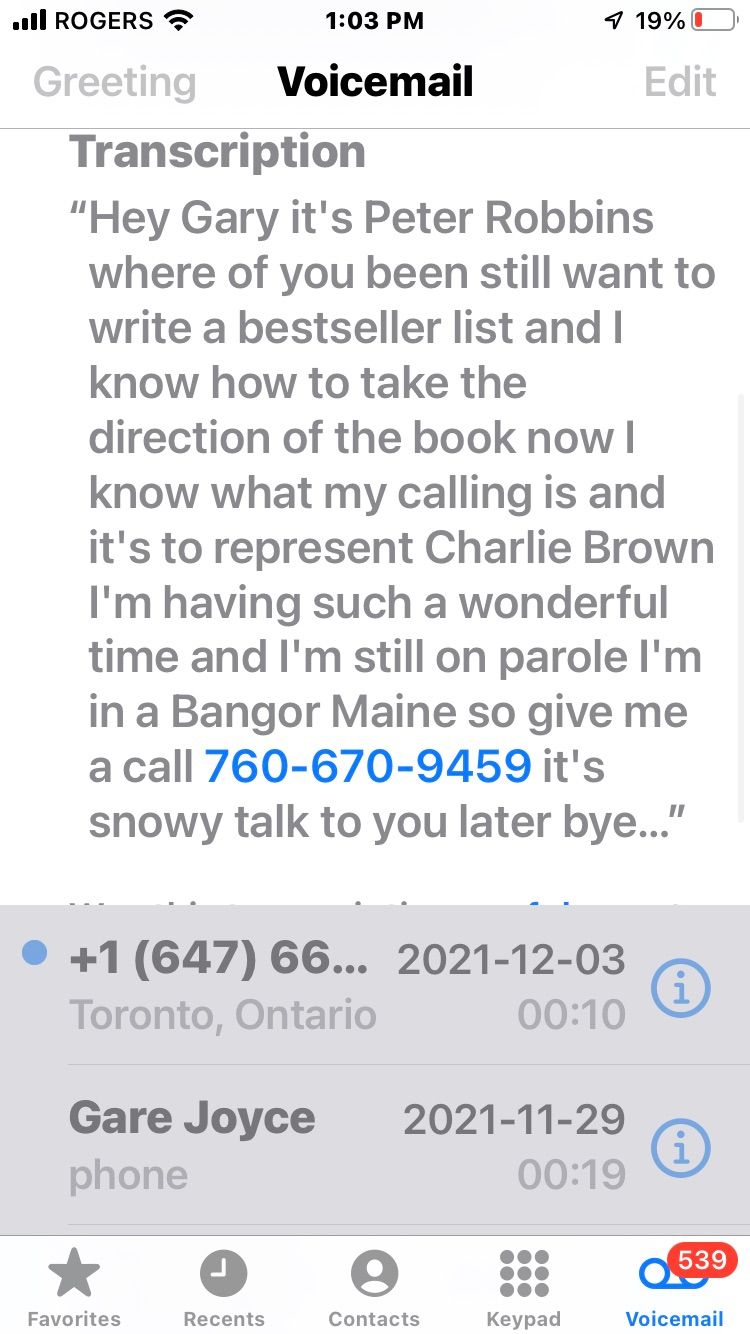

“Hey, it’s Peter. Where have you been? How are you doing? Are we still going to write that best-seller? I know how to take the direction of the book now that I know what my calling is and it’s to represent Charlie Brown. I’m having such a wonderful time and I’m still on parole. I’m in Bangor, Maine. It’s snowy. Give me a call. Talk to you later.”

That message left in December last year is still in my inbox. I can see Peter’s name as it’s listed in my iPhone’s directory of contacts.

760-670-9459 Escondido, California December 10, 2021,

I took a screenshot of that. I use it as my screen saver.

I’m like a lot of people: As a kid, I loved Peanuts, the Charles Schultz comic strip. It started when I watched A Charlie Brown Christmas the first time it ever aired. It was 1965. I was 9. My parents had a black and white TV and it didn’t matter. From then on it was the only Christmas story that mattered to me. I remember the first words that Charlie Brown spoke in that croaky voice, impossibly defeated.

“I think there must be something wrong with me, Linus. Christmas is coming, but I'm not happy. I don't feel the way I'm supposed to feel.”

After watching A Charlie Brown Christmas, I got our copy of the TV Guide, pulled out the page with the listing of the show and taped it on my bedroom wall. I was an early-onset obsessive fan of the comic strip. All through grade school, when I picked up the newspaper, I turned to the funny pages and found Peanuts. Other comic strips had corny laughs, like the hapless soldier Beetle Bailey or the cavemen in B.C. Pogo looked neat, but the political satire soared over my head. Really, though, I only cared about Peanuts. The minimalism sucked me in before I knew what minimalism was: the simple line drawings, imperfect shapes but perfect expressions. Where the strip was set was never mentioned but it didn’t have to be. It was everywhere.

I bought little paperback collections that Crest Books published. The titles sounded like words of consolation for a kid on a lifetime losing streak: Nobody’s Perfect, Charlie Brown; You Can’t Win Them All, Charlie Brown. What Now, Charlie Brown? Take It Easy, Charlie Brown.

My favourite Peanuts character was Pig-Pen, the scruffy kid standing in a cloud of dust. In a Charlie Brown Christmas, he built a dirty snowman. In the Great Pumpkin Halloween, he wore a sheet as a ghost outfit, but all the kids knew it was him because of the dust billowing out at his feet. I sympathized with Charlie Brown but I identified with Pig-Pen. As a kid, I had a dirt thing. When I was a pre-schooler, I used to like to dig holes. I would go in the backyard with my shovel and dig holes so deep that I needed help to get out of them, dangerously deep now that I look back at it. My bond with Pig-Pen wasn’t just soil-based. I admired his attitude, his intellect, his wit. He was never the centre of attention—he was at the side of the panel, offering commentary, the schoolyard philosopher. Oblivious to his appearance and the world around him, He lived in the realm of thought.

An early appearance in the Peanuts strip, established the character in four frames: Pig-Pen is sitting in a mud-puddle, reading, while two girls walk by, mocking him on their way,

“Isn’t he awful?”

“Terrible, just terrible.”

“A real good-for-nothing.”

“I’ll say, a complete flop”

When they walk out of the panel, Pig-Pen, now standing in the mud puddle with his book by his side, says plaintively: “I’m well-read.”

My family and friends would look at this and tell me that they could hear me say that. “Totally you,” they’d say.

I collected Pig-Pen memorabilia: ballcap, t-shirts, figurines and, most treasured of all, a rough sketch of Pig-Pen drawn by Charles Schultz and an animation cel featuring him from a 70s commercial for Regina Steamer vacuums. The artwork is authenticated and to my mind should hang in the Louvre.

If the story stopped here—a grown man with a comic-strip character as his fetish—it wouldn’t be much of a story, I guess, but things turned unexpectedly for me in November 2008, almost forty-three years after I watched a Charlie Brown Christmas for the first time, I was in Oceanside, California, on work assignment.

Up early, still adjusting from Eastern time, I headed to the nearest greasy spoon and while nursing a coffee I struck up a conversation with a neighbouring diner. He said he was a property manager of rental homes in the area. I told him I was a sportswriter—that I came to San Diego to write a high-school football story.

“Such a cool job,” he said. “I’m a big Chargers fan. I did some radio in the market here years back.”

He doesn’t have much of a radio voice, I thought, but I let it slide.

He said I should give him a call and maybe we could watch the game at high school Friday night. I figured I might be able to tap him for some local knowledge. I didn’t have a business card to give him, but he gave me his.

PETER ROBBINS PROPERTY MANAGER OCEANSIDE

The light bulb flashed, like it would in a comic-strip thought bubble.

“You’re the Peter Robbins.”

It didn’t immediately register with him. He looked puzzled.

“The voice of Charlie Brown. The original.”

“I am,” he said. “You’re the first person I’ve ever met who put it together, just knowing my name. Like in real life, not at a Comic-Con.”

“You were Mr Big, the kid genius in Get Smart, and Eddie’s best friend in The Munsters,” I said.

I rolled through all his credits as a child actor in Hollywood back in the 60s. And I went through the names of cast that voiced a Charlie Brown Christmas. Weird by the standards of most people in the street, but standard stuff among pop-culture obsessives who’d actually go to a Comic-Con.

A lot of former child actors whose celebrity lasted Warhol’s metaphorical 15 minutes resent talking about their pasts. Peter embraced his. He rolled up his sleeve to show me a tattoo of Charlie Brown and Snoopy. He pulled out a photo of his dog, yes, a beagle. He told me that he had recently connected with Christopher Shea, the voice of Linus, and they had planned to get together for the first time in years to go see an Eagles concert.

“You know how much I made from a Charlie Brown Christmas?” he said. “A hundred-and-twenty bucks. No royalties. We recorded it after school one week.”

This I knew. I had read about the child voice-actors getting stiffed. A key role in a piece of broadcasting history and only $120 to show for it: This might have been the most Charlie Brown thing of all time, right up with Lucy pulling the football away from him on every field-goal try. Yet Peter wasn’t bitter about it. “How could anyone have known?” he said.

The more Peter talked, the more I could hear that voice from the Peanuts Christmas special. It hadn’t changed that much. Just think of Charlie Brown’s voice—it’s hard to imagine that croaky, world-weary voice coming from a nine-year-old. He sounded like a luckless adult in grade school and much the same in his 50s.

And looking at Peter, well, not to be unkind but he had a passing resemblance for Charlie Brown—male-pattern baldness had left him a little tuft high on his forehead, a match for the squiggle that was Charlie Brown’s hair. What set Peter apart from the character, though, was his laugh—the only laughs in Peanuts specials were laughs at Charlie Brown’s expense, ever the object of childhood ridicule. Peter, though, could laugh.

I stayed in touch with Peter thereafter. He became one of those social-media long-distance friendships—someone you meet once but never quite reconnecting in person, though never falling completely out of touch.

A message on Facebook. A text about the Chargers. A couple of times a year a phone call. “Are you coming to San Diego anytime soon?” he’d ask.

When I spoke to him on the phone, I got a sense that things weren’t going so well for Peter—he was up and down, sometimes sober, other times half-hammered or high or both. I didn’t know how deep that ran. I figured I was just a name in a drunk-dial directory.

A few years after we first met Peter called me up and asked me if I’d ghost-write his memoir. “How’s this … Confessions of a Blockhead,” he said. I loved the idea—every year publishers release books about Charles Schulz and Peanuts. When he started talking about bringing in Phillip Morris, the big Hollywood agency, and a potential movie, I tried to rein in his expectations. I told him his memoir wouldn’t be a best-seller, but it could do healthy numbers and it would be something for him to sign and sell at Comic-Cons.

I worked away on a proposal and a couple of sample chapters that we could shop to publishers. It was slow-going. Peter would ghost me sometimes when I had a question and would never get around to reading what I had put together. I wasn’t worried though. We weren’t facing any deadline, I figured.

The memoir hit a wall in 2013. I hadn’t heard from Peter in three or four months and then one morning I read an online-news story that he had been charged with making threats to his ex-girlfriend and her plastic surgeon. TMZ made him a punchline:

A Charlie Brown Arrest WAH WAH Voice Actor Busted for Stalking

Peter’s lawyer arranged a plea bargain and a judge sentenced him to probation—he was free to go as long as he did time in rehab, stayed clean and got psychiatric help. Somehow, in the years I’d known him, I had missed the fact that Peter Robbins was mentally ill—addiction, depression, schizophrenia and bi-polar, all in a cluster.

Strangely, this brush with the law seemed to motivate Peter to tell his story. We were on the phone weekly and I had three chapters ready to shop. I keep copies of them on my desk, these days.

The first one I put together focused on the day of Peter’s audition for the role of the Peanuts show:

I was a little annoyed when my mother pulled me out of my third-grade class an hour or so early on the day that would forever echo through my life, that would follow me everywhere I went, that would make me recognizable to millions only if they closed their eyes and listened to my voice. Not that I had any sense of that it would play out like this—at age eight, who among us sees a big picture beyond the schoolyard and the playground.

There was no making him an innocent, mind you. He wasn’t just precocious. He was a professional.

Even at age eight, I knew the difference between a movie and a TV series or even a pilot. I knew the difference between a recurring role and a guest shot. This one, though I wasn’t really sure about. For one thing, it was voice work for a cartoon rather than performing on camera. For another, it wasn’t for a movie or a series, but just a one-off half-hour show. I had never done anything like that before. I was a competitive kid. I took satisfaction from getting a part. I’d see the same kids at cattle calls for movies and shows—we all knew each other from waiting for our names to be called. At the end, if I landed a role, I knew that I had been chosen and even that I had been chosen and they hadn’t.

There was a sense of foreboding.

My mother told me that it was based on a comic strip: Peanuts. I had read it before and I read it a little more closely before the audition. Yeah, intuitively I knew about researching roles. When my mother told me that I was up for the role of Charlie Brown, well, I had mixed feelings about it. I told her that I didn’t like that he was such an unhappy kid, that others made fun of him, that bad things just seemed to always be happening to him. It was the lead role, though, and that meant a lot.

I thought we were making real progress but then came a call that rocked me. Peter sounded despondent and was talking about suicide, I was sitting in a crowded coffee shop and this was no conversation to have in public so I stepped outside—it turned out to be a brutal winter day. With the wind howling, I tried to do the emotional support as best I could. Then, right before he hung up, he cut to the chase.

“You might not hear from me again,” he said. “I’m going to court.”

I tried calling back. He didn’t pick up.

A few days later, I was scanning the entertainment news and saw a wire story from San Diego: Peter Robbins was going to prison. I Googled his name and “stalking” and “threats” and found a video of his sentencing that had aired on the local California station. a scene in the courtroom. Peter was unhinged, yelling, f-bombing the judge, telling him, “I hope you die.” And, yeah, if you listened hard enough, you could hear the voice of Charlie Brown in there, saying stuff that would never land in a Peanuts script. That must have aggravated the judge, who sentenced Peter to five years in Chino state prison.

A couple of months later I sent a letter to Peter, care of the prison. I didn’t get a reply. I posted messages on his Facebook page, where his friends and fans left messages, saying how much they missed him. Every August, I’d wish him a happy birthday on the page. In his profile photo, he was sitting on the beach with his back to the camera, wearing an orange t-shirt with a black zigzag across the bottom just like Charlie Brown’s and holding his white and black beagle Snoopy beside him.

I thought that I’d never see or hear from Peter again.

In 2019, after serving more than four years in prison, Peter was paroled and a month later, after he had settled into a halfway house, he called me.

Peter sounded good. He said that the psychiatrist he was working with had come up with the right prescription. “He figured out my brain chemistry,” he said. “I haven’t felt this good in years.”

“Are you still interested in working on the memoir?” he said. “Now I have a real story to tell. I’ve got a new title, Dog Meets God.”

I felt like I had to do whatever I could to support him in his recovery, whether the book flew or not. Geography was the enemy here. He was in San Diego and I was in Toronto, so I thought we’d still have this long-distance connection, hours on the phone. Then Peter told me that the parole board had granted him an exemption to travel for work and in this case, work was a Comic-Con in Providence, Rhode Island.

“If you can do four years in prison, I can drive to Providence,” I said. The plans were laid: 10 hours of interviews across his three days at the event. We’d meet at a steakhouse beside his hotel on the Thursday night he flew in.

I had missed signs of Peter’s mental illness when we first met but I couldn’t miss the signs that his recovery might not be taking.

When I tracked him down, Peter was sitting alone at a table with the voucher the Comic Con organizers had given him for a comped meal. At the table beside him were a bunch of regulars on the Comic-Con circuit, including: Dan Ruettiger, the real-life Notre Dame football who inspired the movie, Rudy; two members of the Village People, Cowboy and Apache; and minor players from Star Wars, like Joonas Suotamo who played Chewbacca.

“Welcome to Hollywood,” Peter said.

It felt more like the Hollywood Wax Museum, but this wasn’t the time or place to get into fame’s best-before date.

When we ordered, I was surprised that Peter asked for the wine list. I assumed that abstaining from alcohol would have been a condition of his parole, not to mention probably wise given the difficulty finding a balance in his medications.

“You’re okay to drink?” I said.

“I’m on Antabuse but this will be fine,” he said.

I was even less assured after dinner, when he pulled out a bag of weed and started to roll a joint under the table. This had to be a parole violation.

“Are you getting urine tested?” I asked, just as an icebreaker. I knew he was getting urine tested.

“This probably won’t show up,” he said without look up as he kept rolling. “Anyway, I really need this. Weed is good for my depression.”

“You know what’s bad for your depression?” I said. “Prison, prison would be really bad for your depression.”

That was as bad as it got over the weekend, though. He was never fall-down drunk, never spaced-out, never disconsolate, never irrational and, most of all, never sounding defeated.

I sat with him for hours at his table on the floor of the convention centre while he signed photos and memorabilia for Comic-Con fans. I served as the bank, collection $60 for each signed photo and selfie. He recorded personalized messages for the fans on their iPhones. The most popular request was “AARGH!” That was his signature, his utterly exasperated cri de coeur. Whenever he did for fans at the Comic-Con, he’d tell them that he “aged out” of voicing Charlie Brown at 14 and 50 other child actors followed him in later shows and video games. “The one thing they kept of mine was ‘AARGH!’” he said. “They edited that in as a sample, because nobody could really match it.”

Even though he was 63, you could hear Charlie Brown in his voice but you could also hear Peter Robbins, the competitive nine-year-old.

Peter was in especially good form when he was interviewed by a reporter from the Providence newspaper—I had made a call to their news-desk and sent an email to their entertainment editor. Peter turned on the charm.

“The credit goes to the man who is actually in the arena, and fails time and time again, like Charlie Brown, to kick a football,” he told the reporter. “But it will never be with those timid souls who neither know the thrill of victory or agony of defeat. That is why Charlie Brown is such a wonderful character. He does see a psychiatrist, so he knows he has got some problems and he is trying to get help. They always say that Charlie Brown is a lovable loser but, at the end of the day, he gathers everybody around the tree.”

Some of it came from the heart, probably a lot of it. Some of it also came from a guy who topped off dinner with a joint and a double Johnnie Walker Black Label the night before. In other words, Peter Robbins was giving a performance, filling the role of Peter Robbins, recovering child actor. As performances go, it wasn’t perfect but it wasn’t cynical either. It was just convincing enough to make me believe that we could make his memoir happen, whether it was Confessions of a Blockhead, Dog Meets God or Good Grief, if real life caught up to the messaging.

When I left Sunday night, Peter was in pretty good spirits—he had made $6,000 over the course of the weekend, less than he hoped, but as he told me, “It beats Chino.” I told him I’d have chapters together about his arrest, his time in jail and his life in a halfway house, which he described as “beautiful, overlooking Torrey Pines golf course, a real swanky neighbourhood.” I promised to sound out my agent and publishing executives I knew, just to get a clear idea how we could make the best possible book into the hands of the most potential readers. We made plans to reconnect in San Diego in the spring.

“I’d tell you could stay at my place but you’d have to go to jail first,” he said.

On my drive back from Providence it dawned on me: At some point, I had become Pig-Pen to Peter’s Charlie Brown. I was his wingman, his sounding board. I could offer observations but nothing more than hollow consolation. I was all the entourage a child star could muster 50 years after his last IMDB credit. I was the dirty ghost.

Three months later, Covid made that trip impossible—there was no crossing the border. Three months later, Peter’s sole source of income dried up—dozens of Comic-Cons dates were cancelled. Three months later, getting in touch with Peter became hit and miss—he was released from the halfway house but a stint in a rehab ended when he relapsed. Every couple of months he’d call and we’d chat, but he said he had no way of reading the manuscript because he had no access to a computer and he was, in fact, homeless. “It’s bad when rehabs won’t have you anymore,” he said.

If you had told me something awful would befall Peter at that point, I wouldn’t have been surprised, but then came that voicemail just before Christmas, when he was in Bangor, Maine. The PBS station there had flown him out to be a guest on its broadcast of a Charlie Brown Christmas. It turned out that a producer there had come across the story in the Providence paper and thought Peter’s real-life story, mostly unknown except for the salacious, was a complement to the animated classic.

“The people here are so nice,” he told me. “I feel like I could move here and start a whole new life. And I feel like I’m ready now to do my book. It has been a lot, but there’s still time.

Peter sounded better than ever, as upbeat as when he sat at the counter of greasy spoon in Oceanside 13 years before. I told him that I was working on a project for Audible and until I had him on the line it hadn’t occurred to me that his story was a perfect fit for an Audiobook: the voice of Charlie Brown talking about struggles when you leave the playground behind, alcohol and drugs only the start of them. As soon as I got off the call, I typed up a pitch for my Audible editor and fired it off. She sounded intrigued and said that it was something we could discuss after Christmas.

It turned out there wasn’t much time at all and the book was never going to get written. An alert came up on my iPhone screen with the tingle of a bell:

PETER ROBBINS, VOICE OF CHARLIE BROWN

I only caught a glimpse of it. Is this a text he’s sending? But then I realized it was a news alert.

… DIES AT 65.

The report cited the cause as suicide. Peter could survive incarceration. He could survive being institutionalized and heavily drugged. He couldn’t survive real life. I don’t know what the breaking point was but he’d had a few of them.

I felt like a failure, more abject than Charlie Brown ever was. There was no chance at redemption in this story, no happy ending to this episode.

I won’t watch A Charlie Brown Christmas this December for the first time since I was nine. I’ve put away all my Charlie Brown tchotchkes. I’ve taken down Charles Schulz’s sketch of Pig-Pen and the cel from the Regina Steam vacuum commercial.

As I type this, I’m not thinking about Peter or Charlie Brown or any of the Peanuts specials. I’m thinking about the last appearance of Pig-Pen in the comic strip. Charles Schulz had already announced his retirement and it was a few months off. Pig-Pen is alone in the strip that appeared on September 8, 1999. He’s sitting in at his desk in a classroom, dust billowing up to shoulder height.

“Well, when I left home this morning, I was pretty clean,” he says.

In the next frame, he’s reading the room, it seems and walking his story back.

“Sort of … relatively … borderline …”

And in the final frame, Pig-Pen, resilient in almost 50 years of Peanuts strips, breaks down. He looks blankly ahead, his faced even inked dirtier than usual. He’s embarrassed, ashamed, crestfallen.

“Absolutely filthy.”

I couldn’t help Peter Robbins. I did everything I could to help. Pretty much … above and beyond … within reason … absolutely futile.